Here’s an oxymoron for you: positive discrimination.

You’d be forgiven for thinking it’s a one-hit-wonder 90s band, or some overlooked Roman Emperor: Positivis Discriminatus (or something. Latin was, like, twenty years ago, people, give me a break).

But then, the Romans probably wouldn’t have set much store against positive discrimination, given their fetish for letting the lions have the gladiators that didn’t run fast enough.

So, definition of P.D. (careful if pronouncing the initials in French):

Source: Collins Dictionary

Look! There we are, ladies. An officially disadvantaged group, and as such requiring special opportunities to presumably make us less, or even – *holds breath* – entirely un-disadvantaged.

All those in favour?

Hmm. I’m not seeing a universal show of hands.

There are two questions that have me hesitating about putting my hand up, too:

- Are women still “disadvantaged” in terms of employment, private sector representation or public office?

- If we think that they are, is “the provision of special opportunities” helpful or not to overcome these disadvantages?

Let’s ponder the first exam question. We have time, after all (no lions snapping at our heels).

Put the loaded word “disadvantaged” to one side for a minute and consider the simple fact that women are half of the world’s population, yet still only earn 77% of men’s income (gender pay gap); represent only 1 in 5 parliamentarians globally (the notable exception being Rwanda, with 64% of MPs female); and head only 26 of the top Fortune 500 companies worldwide.

Even in Iceland, top of the Global Gender Gap Index (which rates women’s health, education, political and economic empowerment) there is still not absolute equality:

And that’s for the countries which are doing well (the UK ranks 26th btw. 26th! Land of hope and glory?).

In the meantime, given current trends everywhere else, we won’t attain global gender equality until 2095 (so only another 80 thrilling years of this blog before there is nothing left for me to write about).

So it would seem the answer to the first question is a resounding: yes, or rather, oui, if you are French politologue Thomas Guénolé:

Source: Le Nouvel Obs

Not only necessary, says M. Guénolé, but urgent. Hmm.

Let us turn, seamlessly, to question number two: what are these “special opportunities” for we underchiennes?

Alas, not a lifelong supply of free sherbet dibdabs, as you might have been hoping.

Rather, special opportunities aim to increase gender parity through one of two approaches: hard (legislation, e.g. quotas, with sanctions for non-compliance, like fines) or soft (“positive action”).

The first is self-explanatory.

The second is more nuanced. It involves wheedling, naming and shaming, creating societal credos for employers or political parties who walk the talk.

Which approach works better, if at all?

Good question: and (surprise!) awful to answer.

The easiest difference to spot is the one that quotas bring about. Consider for example local elections in France: laws passed in 2000 and 2007 (financially penalising parties who do not put forward equal numbers of female and male candidates) have had clear results.

And Rwanda’s gold star on gender parliamentary parity, mentioned earlier, is another success to be chalked up to quotas: an obligation for 30% of all electoral candidates to be female.

But “soft” measures can work, too. Take for example the UK’s voluntary 2011/2014 Codes of Conduct which encourage (but do not oblige) recruitment of female candidates to boards. This campaign has doubled the number of women on FTSE 100 boards from 12.5% in 2011 to 23.5% in 2015.

Whatever the approach, results like those are not just good for the women in the roles; they are good for young women needing role models. Ambition is driven in part by our assumptions of what we can or can’t do, so seeing other women going forth and multiplying in sectors or positions traditionally dominated by men can only be a good thing.

Or, as IMF head Christine Lagarde put it,

“La marche d’escalier est tellement haute, qu’il faut faire quelque chose”

Quite.

Alright, then. Sounds straightforward enough: slap on a bit of positive discrimination, achieve gender parity.

Right?

I guess that depends on your definition of job done. Take your child to accident and emergency because they’ve tripped over a rake and banged their head, and the doctors will treat the injury. But if we don’t want to see the same injury again, or other kids coming in with the same problem, we surely need to deal with the underlying issue: put the rake away.

(I know: analogies just don’t get any better than that).

The point (in case you understandably missed it) is this one: positive discrimination, especially the “hard” version, treats the symptoms, and not the causes, of gender inequality.

And thus can actually be harmful, for several (non-garden-tool-related) reasons:

- For each individual woman owing her election/scholarship/job etc under a system of positive discrimination, who will always be suspected of being there on selection, rather than on merit. As Hayley Downing, Associate Director of Investigo, commented: ‘While I am passionate about gender equality in the work place it is important to note that women do not want to be a statistic. I was previously offered a role with a company where the Managing Director said “we really want you to join our business as we don’t have any female Directors at the moment”. While it was flattering to receive an offer from a global organisation, I want to be hired for my skills and ability, not my gender.’ Well, I get that – don’t you? Who does want to be a statistic to serve the greater cause?;

- For women overall, with the paradox that once positive discrimination legislation is passed, it is assumed there is no more discrimination to fix; passons à autre chose;

- For the cause overall, if the woman benefitting from the measure is actually mediocre, and far from the best candidate;

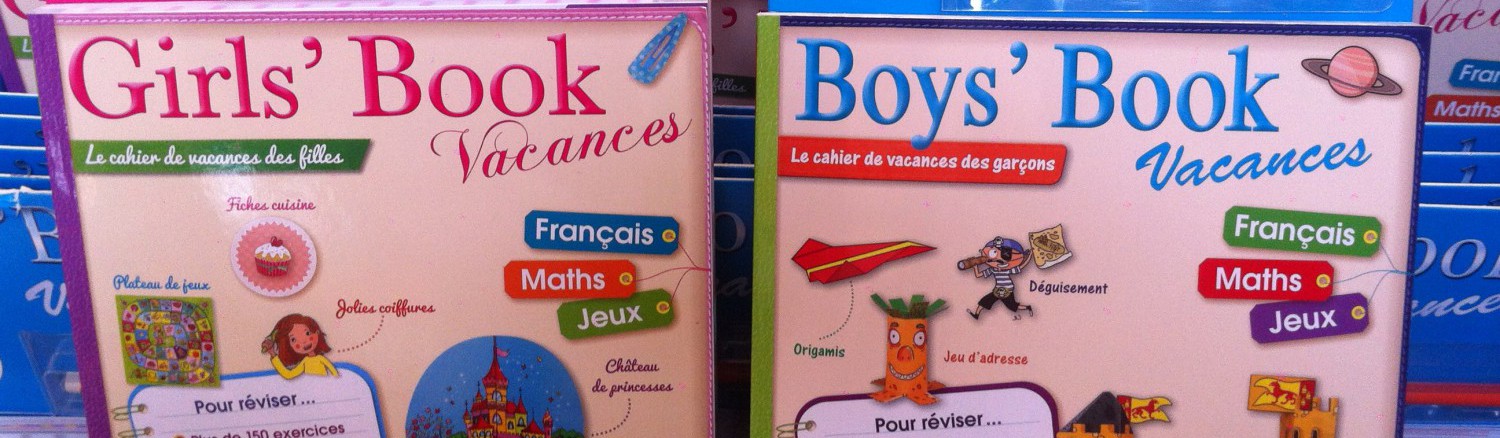

- For tackling the causes of the cause (as per the genius rake analogy). If we lack parity, there are reasons for it: what do we need to change? Parental leave? Gender stereotypes? School fees? Employers’ attitudes?

And yet.

Yes, thèse, anti-thèse: I still can’t help thinking that things will not improve spontaneously, all by themselves. And that until they do, a temporary bias is necessary, and (longer-term) beneficial.

So: all those in favour of positive discrimination?

I think my hand is tentatively up.

Is yours?

Really good summary of the issues! I guess the interesting one will be to see what happens if a country with positive discrimination policies then withdraws them. Will they have been enough to change attitudes or will there be back-slip?

I guess the other worry is about whether ‘une forme de discrimination peut en cache une autre’. I remember going to a trade union event in Paris where yes, they had moved away from just having 200 white middle-aged men on CDIs. Now there were about 100 white middle-aged women on CDIs too. The only ethnic minorities were on security… Is the answer then to implement positive discrimination (hard or soft) in all cases?

LikeLike

Pingback: The F Word | Ze F Word

Pingback: It’s a man’s world | Ze F Word