Here in France, summer has slipped very suddenly into autumn. What I have been wondering since I first put the central heating on (I held out to just-before-October) is whether the change in temperature might bring an end to a lively debate of recent weeks: the skirt.

It began with a social media campaign launched by (female) high-school students protesting against signs forbidding short skirts or crop tops at school (for British readers: there is no school uniform in France, even though a majority of people are in favour of introducing one).

French Feminist commentators such as Titou or Rokhaya Diallo – the latter in an opinion editorial for the Washington Post – reacted angrily. How was it possible in 2020 that women and girls’ vestimentary choices were being policed, yet again?

Over the centuries, what a woman wears has been tightly controlled, as a reflection of her reputation, status or occupation, and that of her husband or family. Covered up or on show; women’s clothing has flowed from whatever gendered fashion notions prevail in the societies and centuries in which we live.

But women’s fashion history has its own evolution, driven by comfort, practicality, religion, or even equality. Heels were originally intended for male actors, in the time of Shakespeare. Corsets have disappeared. Women can wear shorts, and trousers.The old-fashioned bathing suits which astonished my daughter on a 19th century postcard of our favourite Brittany beach have given way to bikinis, topless or even fully-nude sunbathing.

This gradual lessening of the prim and proper means women are freer in terms of the variety of what we can wear. But regardless of these changes – or perhaps as a result of them – the expectation remains for women to align to a set of often contradictory, and mostly impossible, standards.

And the more of a woman is on display, the more there is to beautify to the deemed standard. In her book Beauté Fatale, author Mona Chollet quotes an American plastic surgeon commenting that she owes her clientele to the fact that fashion is constantly lower-cut or more tight-fitting.

And the skirt, in all of this?

Skirts can be sassy, flirty, businesslike, severe, fun or elegant, but all of them definitely emphasize one quality; and that is femininity. There was a time when the European women wore nothing but dresses and skirts, even to the point that the word “skirt” became slang for “woman” in the English language.

https://www.lifeinitaly.com/fashion/skirt-history/

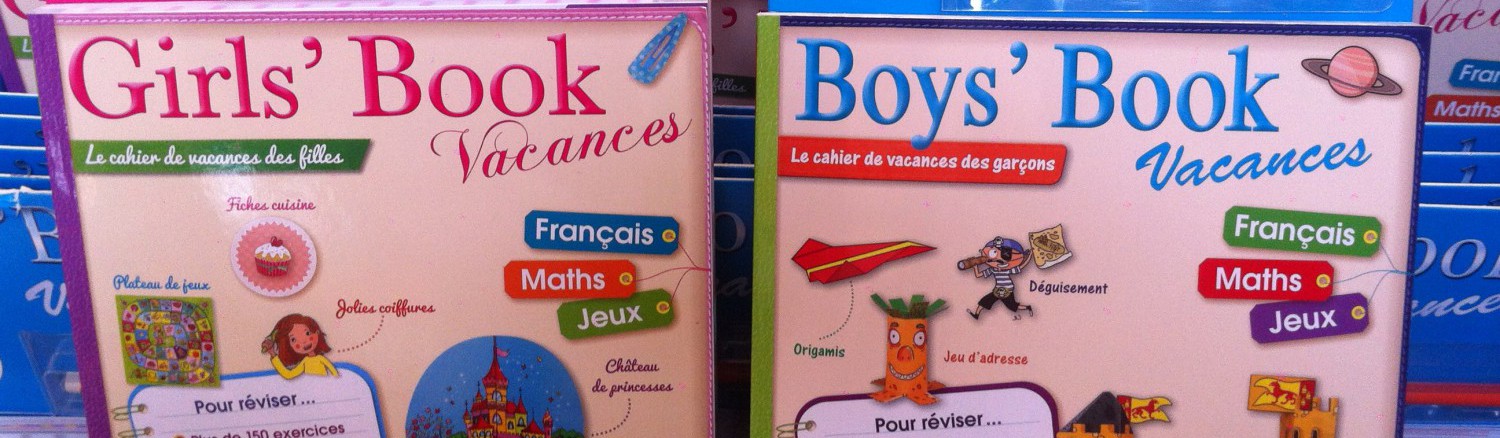

And yet skirts were not always a synonym for femininity. Up until the 14thcentury, they were gender-neutral, as the Victoria and Albert Museum reminds us. Things evolved with the arrival of tailoring, and horse-riding, mostly reserved to men, and for which loose garments were unpractical. Children of both sexes, however, continued to wear long skirts or dresses, up until the 19th century, until the rite of “breeching” was established (the first pair of trousers for boys aged between 4-7), reflecting a new consciousness about masculinity and femininity.

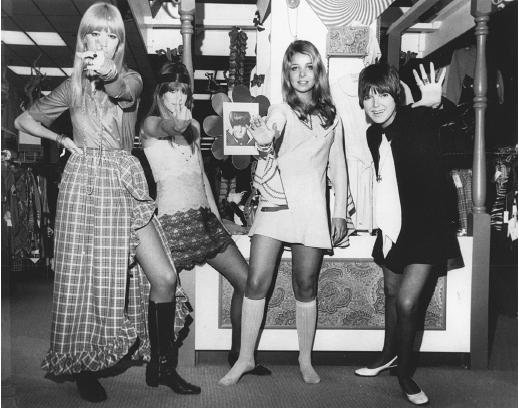

And from there, to the skirt as an exclusive of women’s wardrobes. Hemlines have gradually shortened on the way, culminating with the breathless invention of the mini-skirt by Mary Quant in the 1960s, sparking debates on decency and liberation.

These debates have not shifted a great deal over the last sixty years; a perpetual tug-of-war between modesty v. (sexual) objectification which plays out on a daily basis in the media or in the streets. Think of Muslim women accused of submission for wearing a hijab; or, au contraire, women criticised for “revealing” clothing. Like two victims of assaults in September in Mulhouse and Strasbourg, whose attackers insulted them for wearing skirts.

Or victims of rape, who are so often asked by police (and even friends and family) “ok, but… what were you wearing?”

(See Dr Jessica Taylor’s book, Why Women are Blamed for Everything, for a frightening tour of how frequent victim-blaming occurs for sexual assault, unlike any other crime).

Anyway. Back to our school-girls in France. In the absence of any clear national guidelines (or uniform), various politicians took to radio and television studios to define dressing “decently”, such as Ile de France (Paris region) President Valérie Pécresse, who said she had nothing against the crop-top (pronounced adoringly in English as croppe-toppe) but school wasn’t about “showing off one’s belly button”.

Pécresse was seconded by household-name French philosopher Alain Finkelrault (aged 71), who confirmed that female skin was indeed a Moste Dangerous Hindrance for boys’ attention. Why, he himself found these croppe-toppe highly “distracting” (somewhat alarmingly: surely that kind of physical reaction to a schoolgirl has health implications, at his age?).

As for the Education Minister Jean-Michel Blanquer, faute de mieux, he eventually fell back on the usually fool-proof formula of “valeurs Républicaines” to guide one’s wardrobe choices, much to the delight of the #lundi14septembre movement.

Eager to contribute to this intellectual challenge of defining the undefinable, right-wing weekly Marianne actually commissioned a poll to see what French people thought about what girls wore to school (along with, tant que tu y es, what women should or shouldn’t wear to work, in the street, or on holiday).

The backlash was immediate at both the questions and the astounding pictograms illustrating them (who has boobs like that? seriously). Surprised at the fuss, IFOP, the polling institute, issued a statement defending the survey as “in the public interest”. Yes, because clearly President Macron could not have continued governing France without knowing whether mini-skirts were acceptable on a beach.

You may be wondering where the boys are in this survey, or in fact, in this debate. Not a single question in the poll examined views on dressing decently for young men. Politicians, like Blanquer, were careful to underline that the idea of “appropriate” dress applied as much to boys as to girls.

But force est de constater that offending male items, such as shorts or hoodies, are symbols of an attitude or fashion-choice, and do not objectify the boy himself. And therein, the difference. A skirt is not neutral, even when women wear it without thinking about it. Neither is the croppe-toppe, however endearingly pronounced.

La preuve: “western” heterosexual men do not generally wear skirts, unless it is a question of religious dress (et encore). Even the stars can’t quite pull it off: think of the gasps over David Beckham’s sarong in 1998, or (twenty years on) the consternation which greeted Jaden Smith’s modelling of skirts for Vogue, such as this existentialist fretting from the New York Times:

(…) there’s no question clothes are one way we order the world. (…) Whatever you do in your private life, clothes are public signals about how to read you. They are part of the social contract. If that order is thrown up in the air, how will we know what snap judgments to make? (…) The fear of semiological chaos (and the force of historical convention) explains in part why clothing norms have held on so long. We want to understand what we are seeing, and we want those seeing it to understand what we are saying.

High-heeled shoes, tight jeans, padded bras (shout out here to Petit Bateau’s range for teenagers, which I discovered while buying underwear for my ten-year-old daughter)… “feminine” clothing, cosmetics and beauty-regimes are a huge consumer market intended to force us to be leg/pubic/grey-hair-free, cellulite-free, fat-free, wrinkle-free. A huge and consuming waste of women’s time, money and self-esteem.

So in defending a woman’s right to wear these things, what are we actually defending? Is the skirt just a skirt? Or is it just another expression of gendered roles which actually binds us in further to restriction and objectification, rather than liberation and equality?

These are questions, not answers. But this debate appears to be more about choice and the challenge of choice, rather than the choice itself. And yet only in a world where my own son can wear a skirt if he wants to, without raising eyebrows (including mine); only in a world where clothing and fashion are not greater forces of nature than nature itself; only in a world where women’s bodies and their sexuality are not constantly judged, objectified or commercialised; only then can we all truly dress as we please, without consequence.

Until then, our wardrobe options remain far from neutral, and our free choice, only partly so.

From the garden of Eden… to fruit of the loom.

If you have children, or are expecting, there are a few frequent questions you will get. Mostly, whether you’re having a boy or a girl (note the order. The opposite still feels strange on your tongue).

If you have children, or are expecting, there are a few frequent questions you will get. Mostly, whether you’re having a boy or a girl (note the order. The opposite still feels strange on your tongue). These were not isolated cases. This

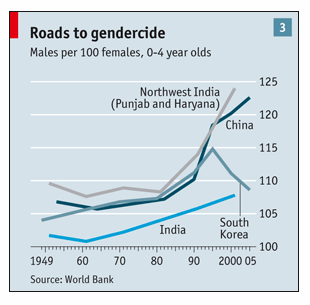

These were not isolated cases. This Three questions, then: firstly, what are these root causes of a preference for boys (especially since they pee over you every time you change them)? Secondly, with what consequences? And thirdly – why so little attention to so many girls and women either not being born, or being left to die, as infants?

Three questions, then: firstly, what are these root causes of a preference for boys (especially since they pee over you every time you change them)? Secondly, with what consequences? And thirdly – why so little attention to so many girls and women either not being born, or being left to die, as infants? It is almost difficult to blame those parents who make the conscious decision to choose an easier life by having a son, especially if their existence is already a difficult one. Especially in countries, like China, where families have been forced to have small or one-child families, where the stakes are so much higher with every pregnancy. Not misogyny, one might reasonably conclude; just financial and common sense.

It is almost difficult to blame those parents who make the conscious decision to choose an easier life by having a son, especially if their existence is already a difficult one. Especially in countries, like China, where families have been forced to have small or one-child families, where the stakes are so much higher with every pregnancy. Not misogyny, one might reasonably conclude; just financial and common sense.

Back in my line-dancing days (don’t knock it until you’ve tried it) an evening wasn’t an evening without a ballad from Shania Twain.

Back in my line-dancing days (don’t knock it until you’ve tried it) an evening wasn’t an evening without a ballad from Shania Twain.

And even with economic and reproductive autonomy, it isn’t easy. Where do you go? Who do you turn to? Especially if you have children; if you are a foreigner or newly-arrived; if you live in communities where local law or judicial services are absent or corrupt; or where there may be an element of shame; or fear of retribution, if there is no safe place to go to.

And even with economic and reproductive autonomy, it isn’t easy. Where do you go? Who do you turn to? Especially if you have children; if you are a foreigner or newly-arrived; if you live in communities where local law or judicial services are absent or corrupt; or where there may be an element of shame; or fear of retribution, if there is no safe place to go to.

The British parent living in France has a great TV bargaining chip: yes, child, you may watch half an hour tonight… so long as it’s in English. I am strict about this, and my daughter has long given up trying to wiggle her way into VF. Noddy is Noddy (it’s Non-Non to Oui-Oui).

The British parent living in France has a great TV bargaining chip: yes, child, you may watch half an hour tonight… so long as it’s in English. I am strict about this, and my daughter has long given up trying to wiggle her way into VF. Noddy is Noddy (it’s Non-Non to Oui-Oui).

We do, inadvertently, have Harvey to thank.

We do, inadvertently, have Harvey to thank.

On the postcard that I forced my daughter to write to her grandmother last weekend was a vintage photo of the beachfront where we were staying. My child peered at the picture, grainy black and white, with its stiffly-smiling, fully-dressed ocean-goers.

On the postcard that I forced my daughter to write to her grandmother last weekend was a vintage photo of the beachfront where we were staying. My child peered at the picture, grainy black and white, with its stiffly-smiling, fully-dressed ocean-goers.